Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music is the first large-scale museum exhibition to illustrate Leonard Bernstein’s life, Jewish identity, and social activism. Audiences may be familiar with many of Bernstein’s works, notably West Side Story, but not necessarily with how he responded to the political and social crises of his day. Visitors will find an individual who expressed the restlessness, anxiety, fear, and hope of an American Jew living through World War II and the Holocaust, Vietnam, and turbulent social change—what Bernstein referred to as his “search for a solution to the 20th‐century crisis of faith.”

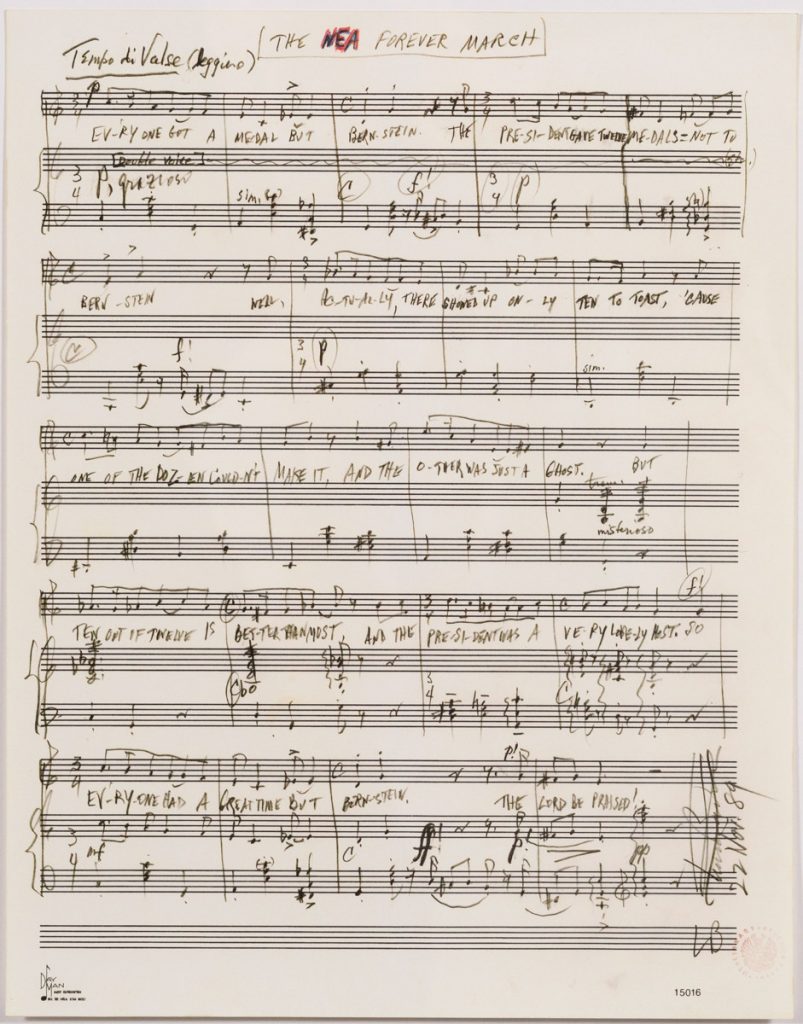

The exhibition explores his Jewish identity and social activism in the context of his position as an American conductor and his works as a composer. It features interactive media and sound installations along approximately 100 historic artifacts, including Bernstein’s piano, marked-up scores, conducting suit, annotated copy of Romeo and Juliet used for the development of West Side Story, personal family Judaica, composing easel, and a number of objects from his studio.

Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music is an original exhibition orchestrated by the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History, Philadelphia, where it was on view from March 16 – September 2, 2018. The exhibition is now touring nationally; you can find the tour schedule here. To learn more about bringing the exhibition to your community, please click here.

There are 9 scenes to explore in detail.

please scroll down to view them in order of the exhibition galleries.

Every image on this site is clickable! Click any photo to enlarge the image, read exhibition text, or explore an object more closely. Click the green plus sign to enlarge an artifact. Click the red “i” sign to enlarge a label. Hear from Ivy Weingram, Curator of Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music through video clips.

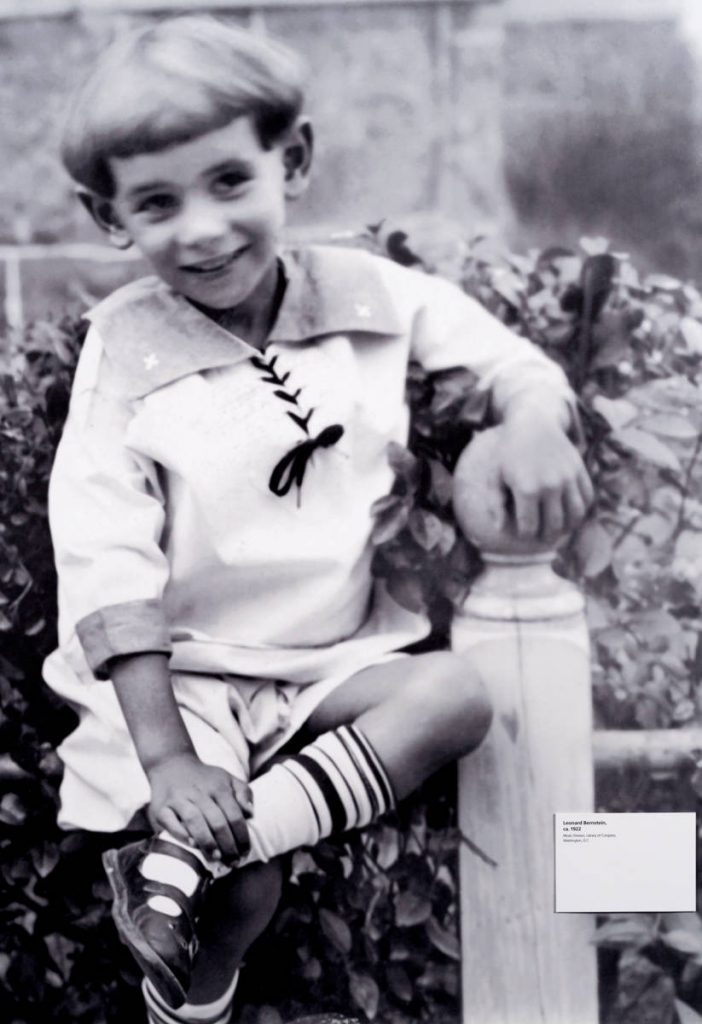

Boston’s Boychik

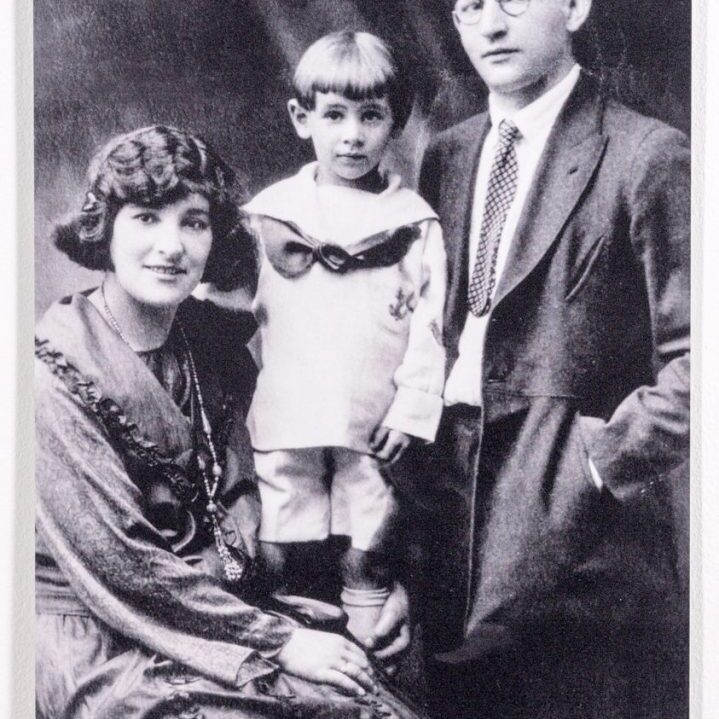

Leonard Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, on August 25, 1918, to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants Jennie and Samuel Bernstein. While Sam pursued the American dream, founding a company that furnished beauty products and equipment to Boston salons, Leonard began taking piano lessons at age 10.

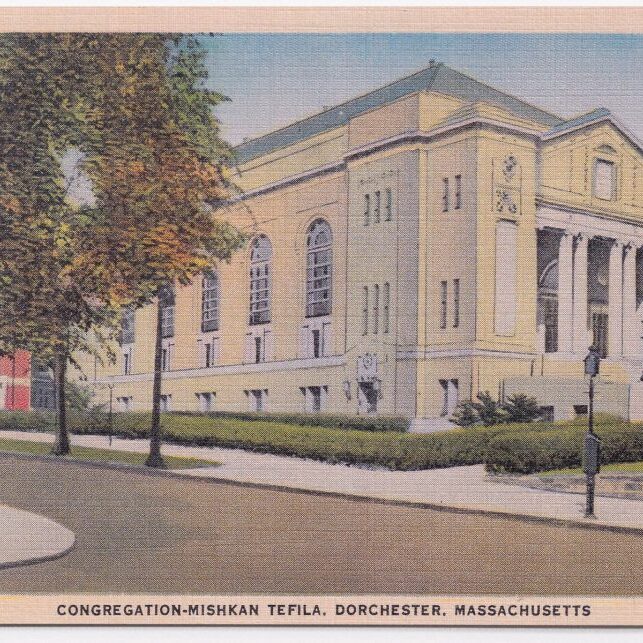

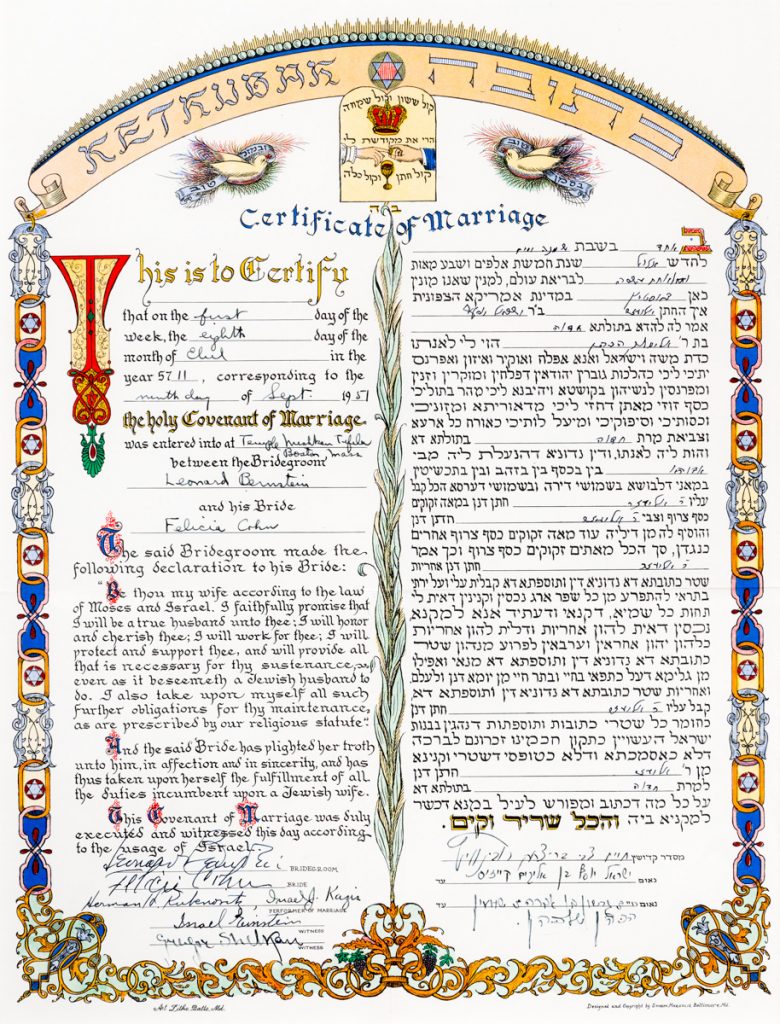

The Bernsteins, including Leonard’s younger sister, Shirley, and brother, Burton, attended Conservative congregation Mishkan Tefila (Sanctuary of Prayer), a synagogue that featured organ music and a mixed-gender choir—progressive approaches to traditional Jewish worship at that time. The community advocated “Liberalism, Zionism, and Social Service,” ideals that would also characterize its native son.

Sam hoped Leonard would one day run the family business, but the piano had become his passion. In Sam’s words, “How was I to know he would grow up to be Leonard Bernstein?”

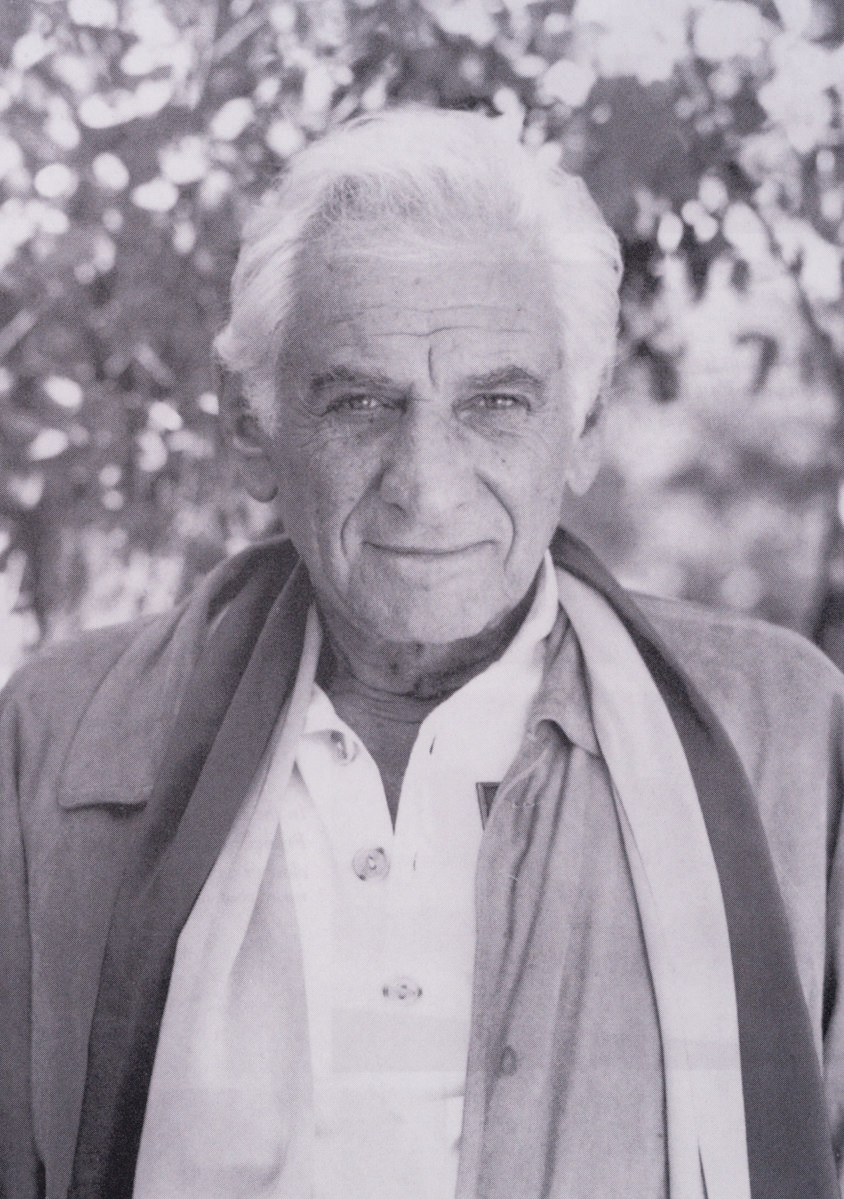

American Maestro

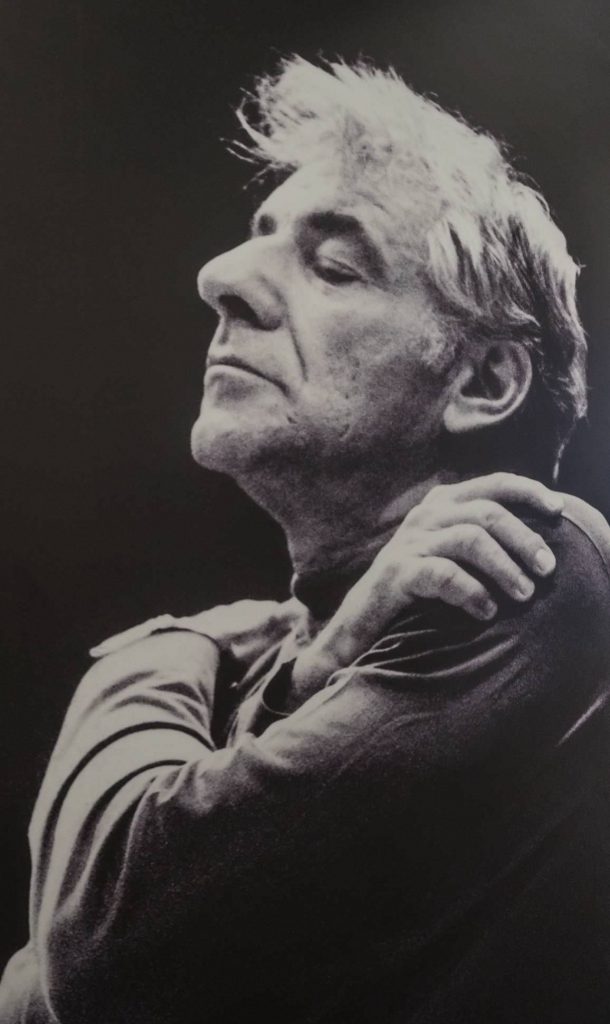

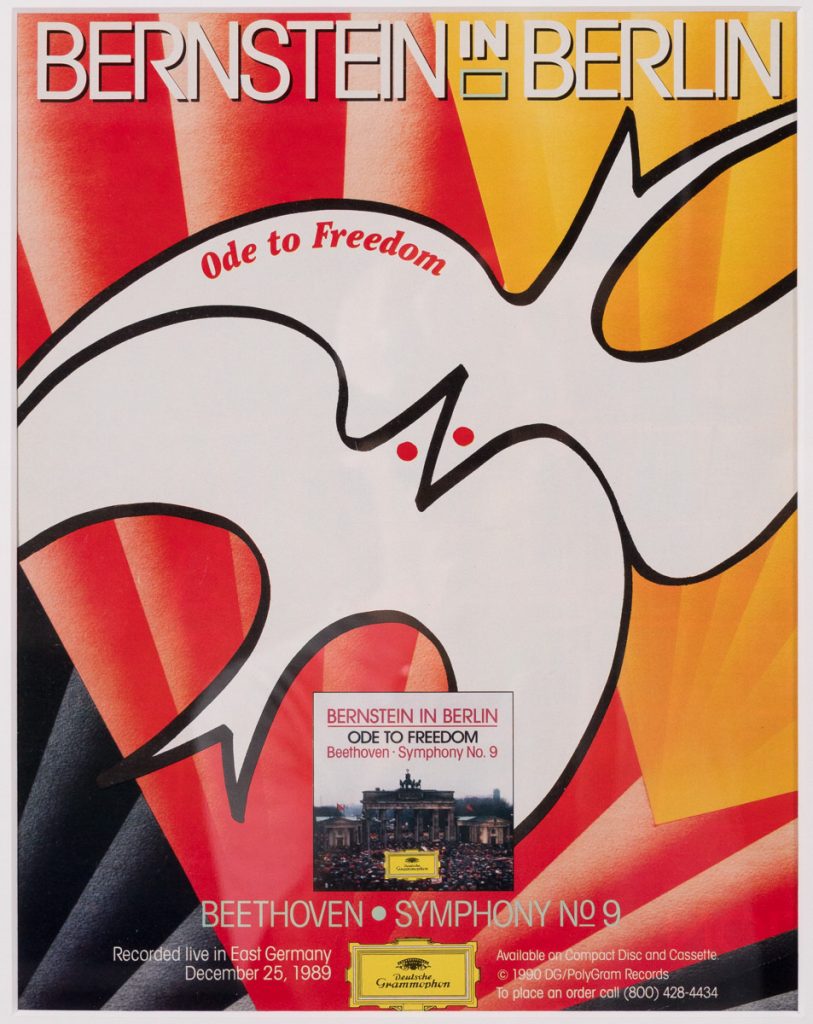

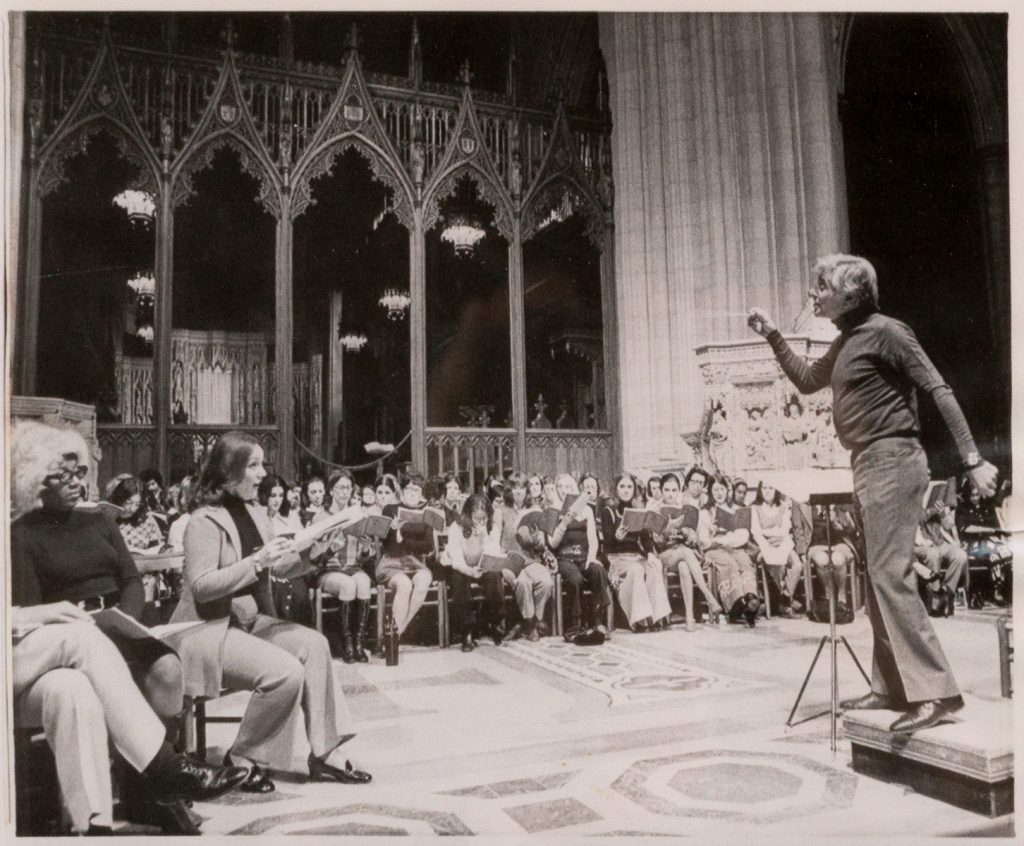

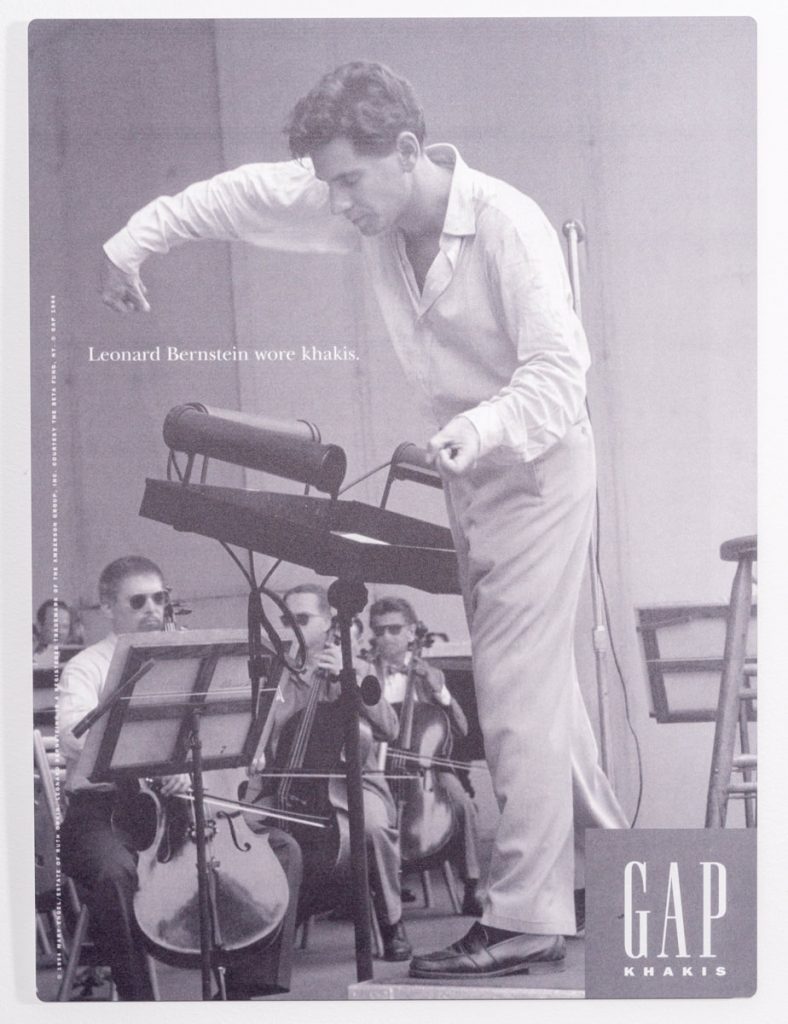

Bernstein was the face of classical music for a generation of Americans. Those who watched him lead the New York Philharmonic in the 1950s and ‘60s remember him as a flamboyant, larger-than-life personality: a charismatic conductor, devoted educator, and skilled musician who popularized classical music in the concert hall and through the television screen. Moreover, Bernstien loved all types of music, and strove to make Beethoven, Bach, and even the Beatles accessible for “students” ages 8 to 80 through his Young People’s Concerts.

He also remimagined the role of the conductor as a vocal advocate for music’s ability to unite communities in times of crisis. At historic moments Bernstein never hesitated to speak his mind first, and let the music follow.

Music Man

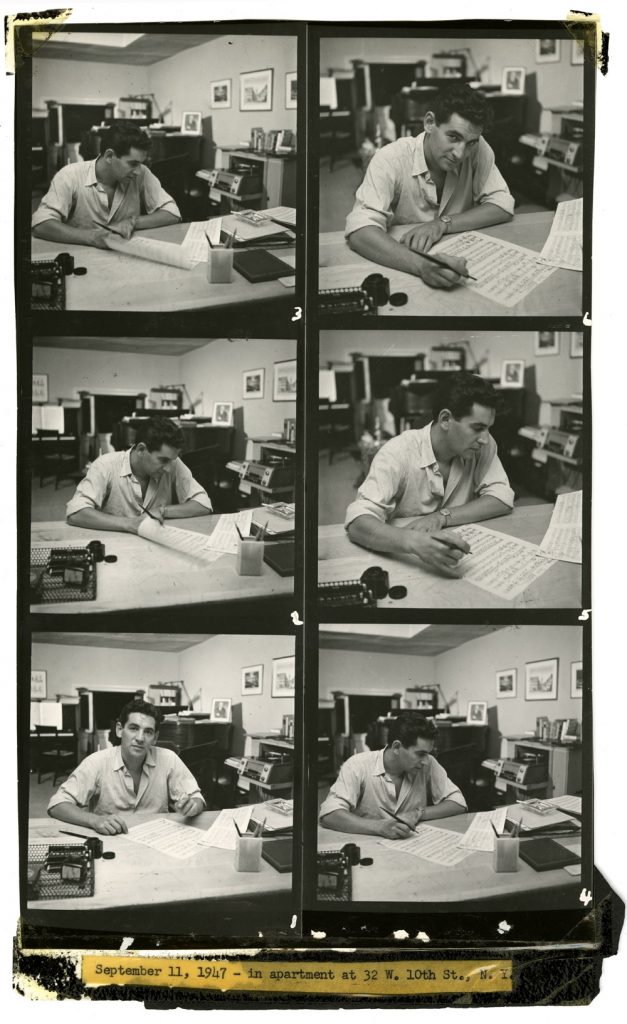

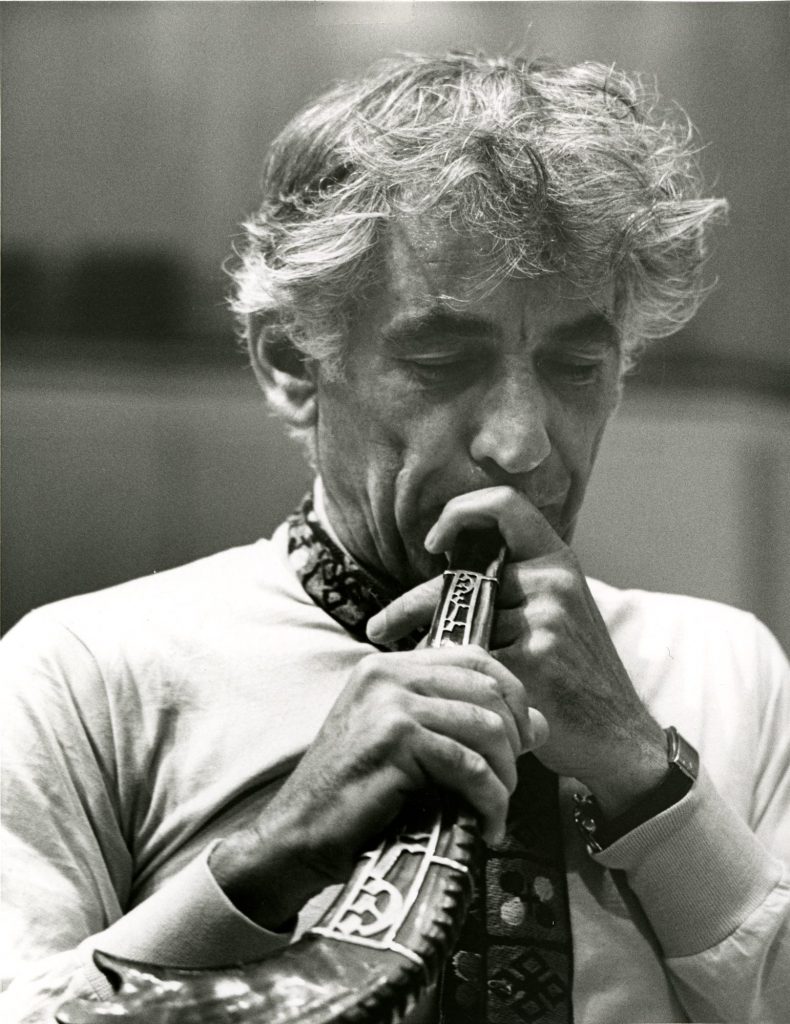

How did Bernstein work late into the night, isolated in his studio writing, even as he spent his days traveling the world as a conductor?

Bernstein channeled his creative passions, anxieties, love of classical and modern music, and fascination with story and wordplay into his original music. There was no genre he was afraid to touch, and like any resourceful composer, he recycled songs and motifs from one project to the next.

For all his accomplishments as a composer—symphonic works, Broadway and film scores, ballets and song cycles—Bernstein never abandoned the fast-paced life of a jet-setting conductor for the quiet life of a thoughtful composer. “When I do one, I long for the other… It’s like being two different men locked up in the same body.”

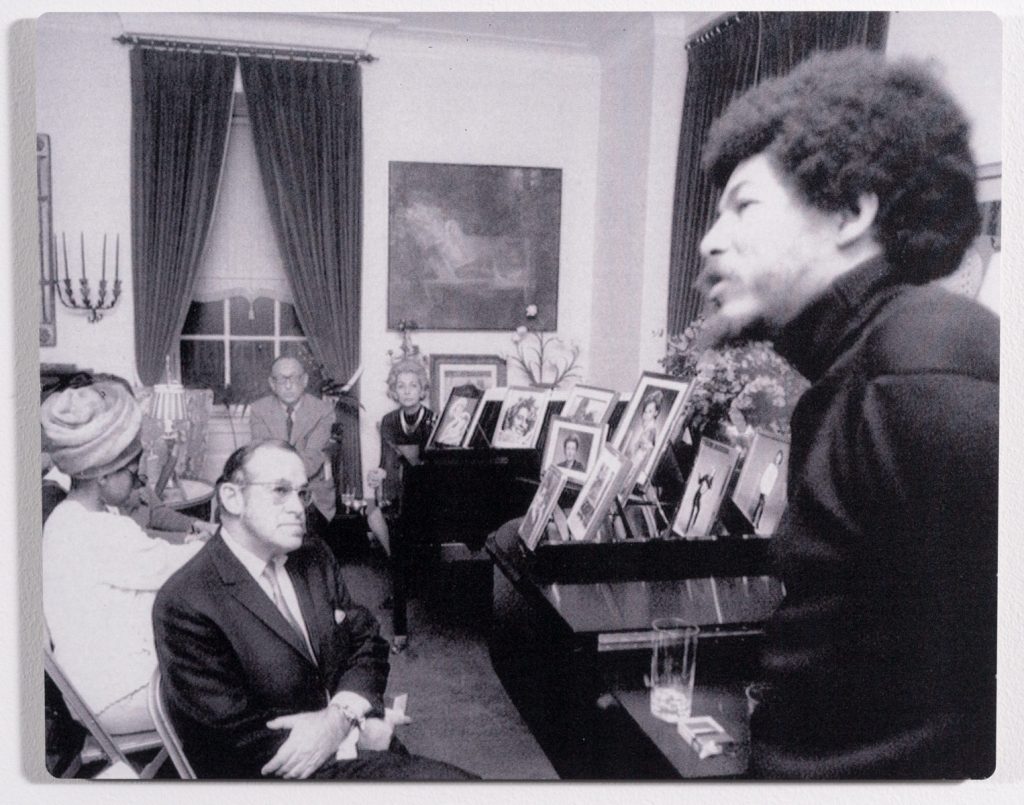

More than Ordinary Courage

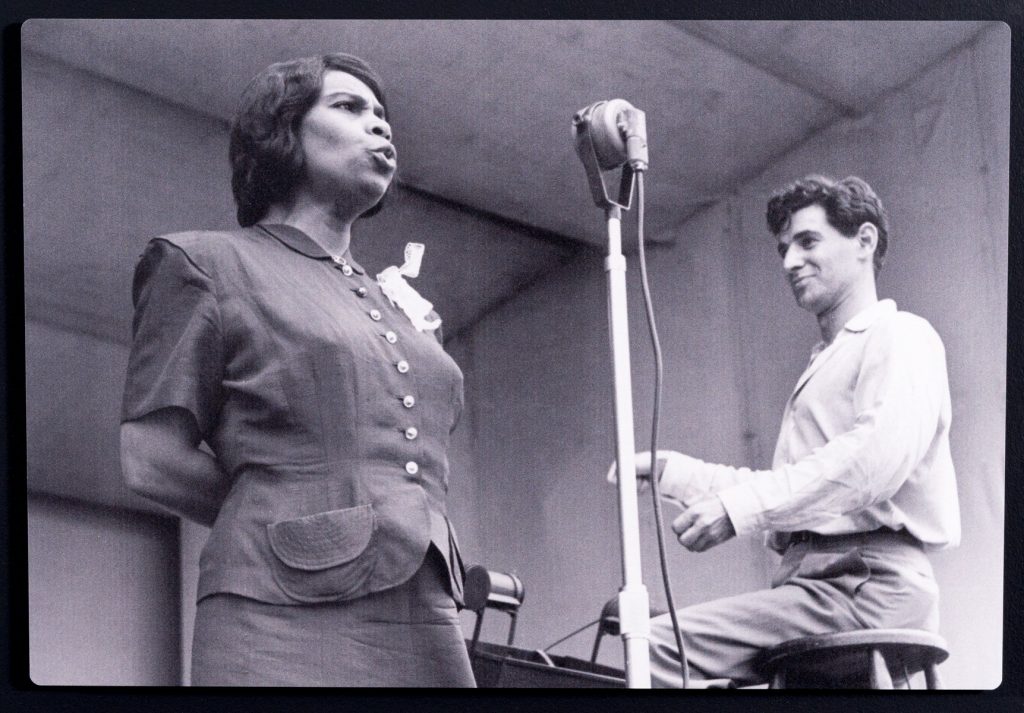

Bernstein continuously leveraged his visibility to advocate for social change. Consistent with his Harvard thesis on American music, by 1947 he had worked with African-American contralto Marian Anderson and with Curtis classmate Muriel Smith, the first African American to study there. In a New York Times editorial that year he argued that racism accounted for the dismal number of African Americans in New York’s orchestras and opera companies.

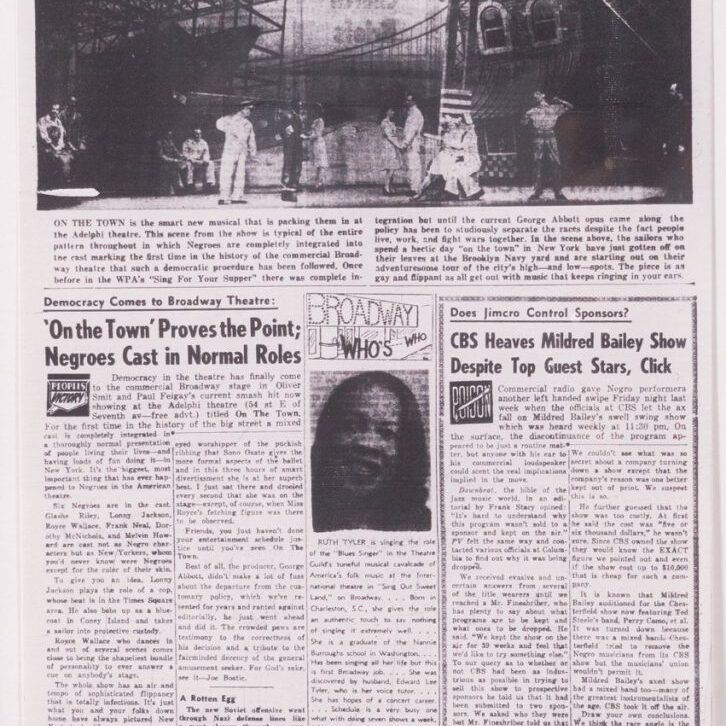

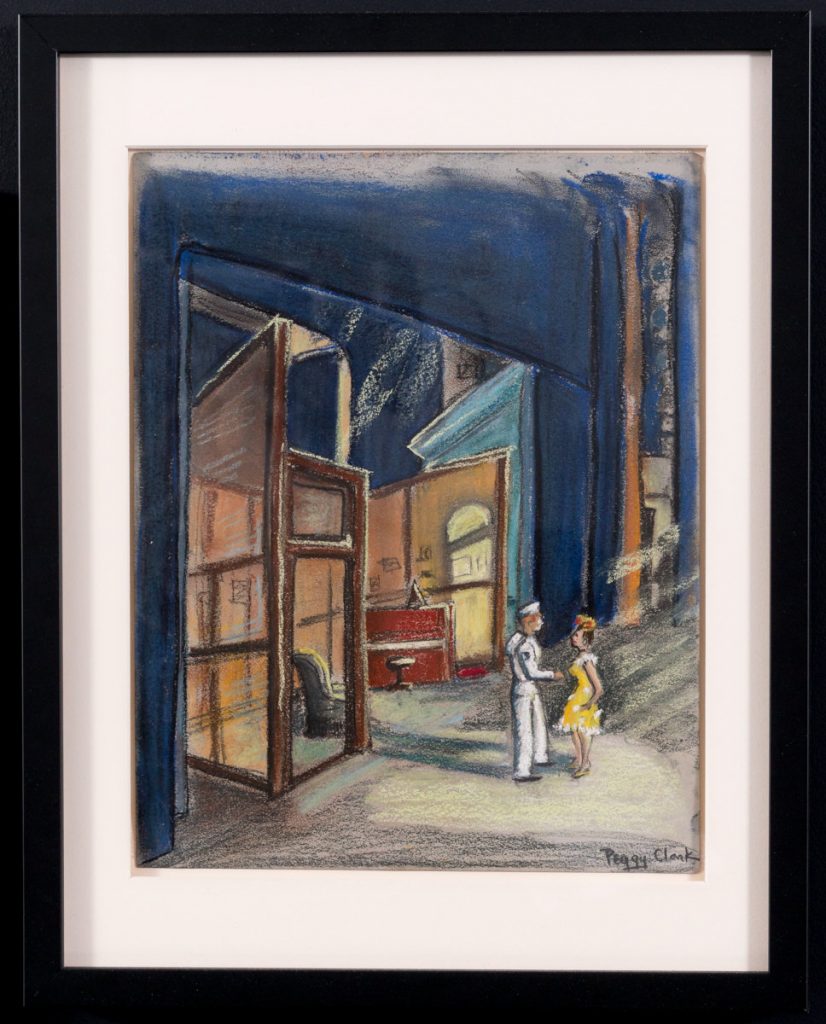

Bernstein entered the Broadway scene with a bang in 1944. On the Town, his Broadway debut, featured ethnic Americans, African Americans, and women in high-profile roles. At a time when laws in many states forbade intimacy between whites and African Americans, members of On the Town’s boldly integrated chorus held hands as they sang the show’s most memorable number and danced their way through “New York, New York, a helluva town.”

An Age of Anxiety

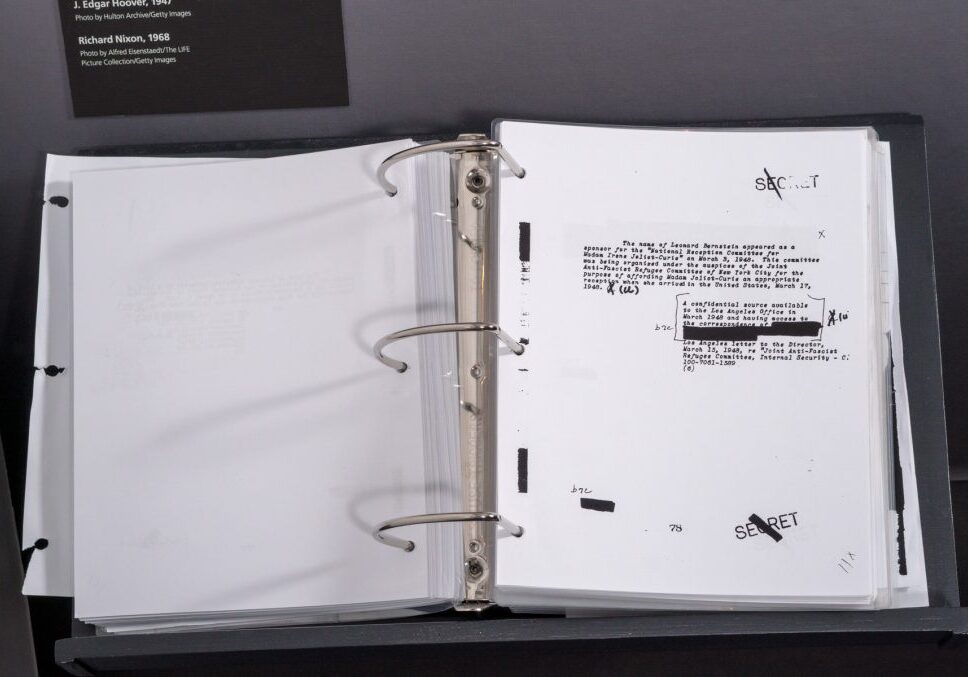

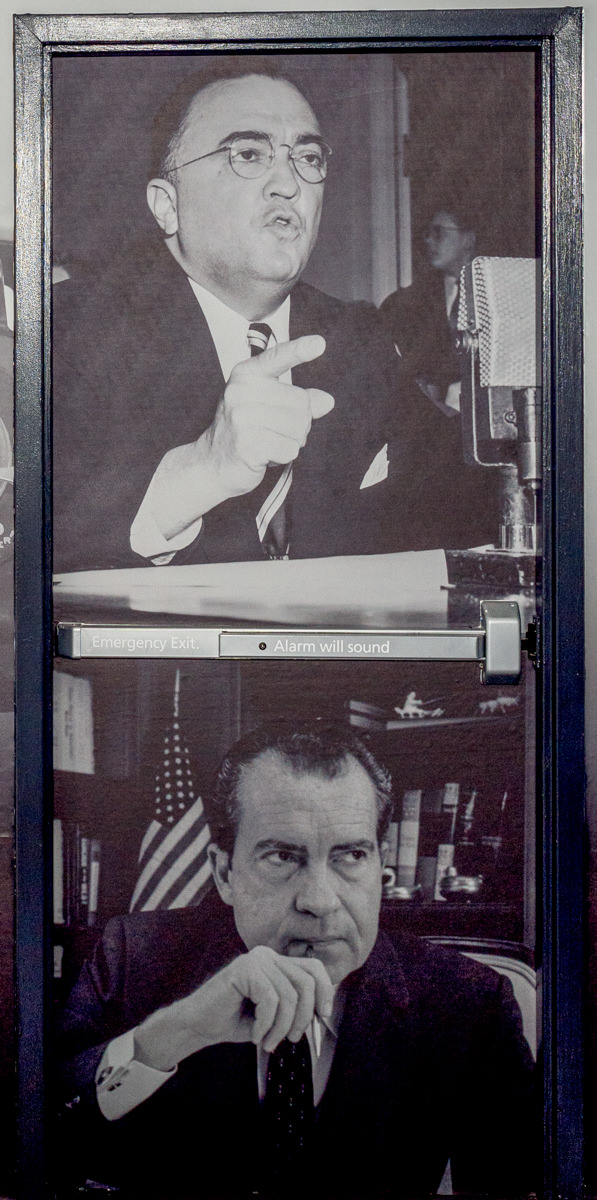

Bernstein felt the sting of Cold War paranoia like many politically active performers and artists. His outspokenness, Jewishness, and social progressivism, coupled with rumors about his sexuality, raised the FBI’s suspicions. The Bureau eventually compiled an 800-page file on Bernstein’s activities, documenting his civil rights advocacy and alleged support for the Communist Party.

What did it mean for a man who proudly wore many badges of American identity—a New England upbringing, a Harvard degree, classical music, and Broadway bona fides—to have his loyalty to his nation called into question? Though his reputation survived largely unscathed, this “age of anxiety” deeply shook Bernstein’s faith—in himself, in his government, and in his fellow Americans’ commitment to equality.

Israel

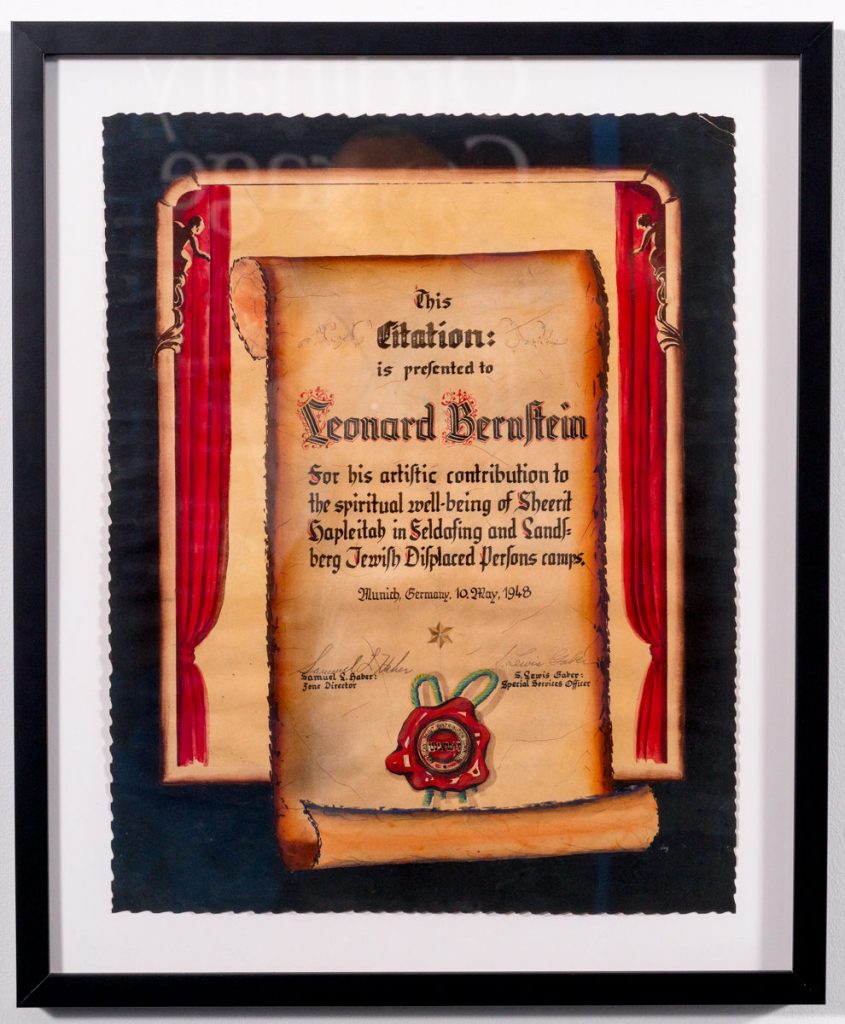

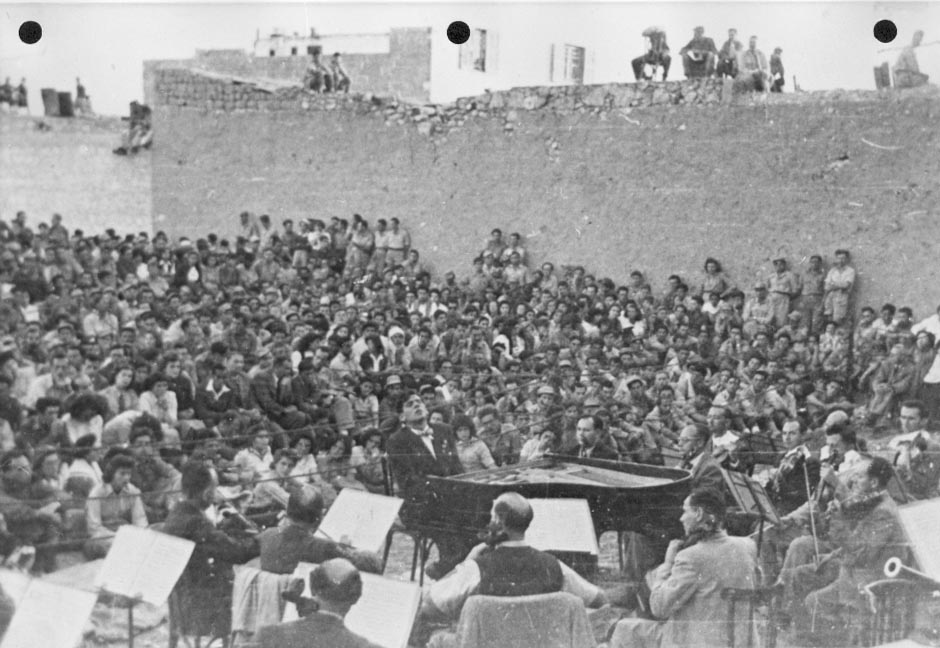

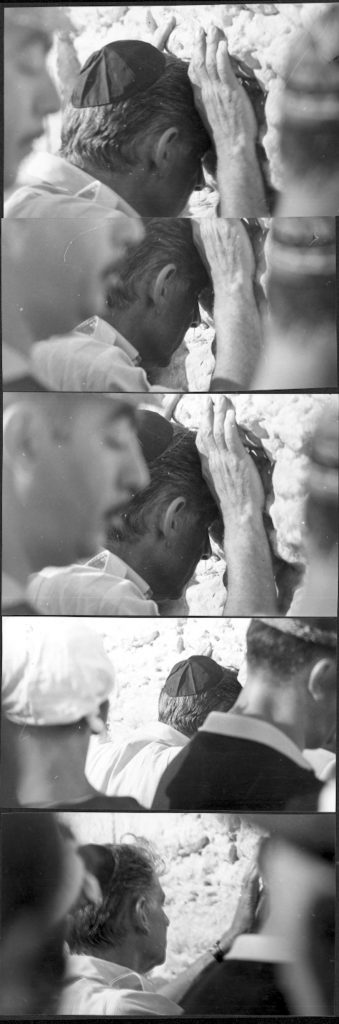

From his youngest days as a conductor, Bernstein committed himself to serving as a cultural ambassador for Israel. The Palestine (later, Israel) Philharmonic Orchestra, composed of Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe, found an early champion in Leonard Bernstein, who had witnessed firsthand the experiences of Holocaust survivors in German displaced-persons camps.

“Israel is a country that looks to music with almost the same need and urgency as to bread itself,” Bernstein wrote. He toured with the Israel Philharmonic in 25 different seasons—more than most orchestras he worked with. Having developed deep bonds with each of “his” orchestras, Bernstein toured and recorded with the New York and Israel Philharmonic Orchestras well into the 1980s.

West Side Story

When West Side Story premiered on Broadway in 1957 it embodied Cold War anxieties and changing notions of what it meant to be an American. Jerome Robbins, Stephen Sondheim, Arthur Laurents, and Leonard Bernstein initially imagined their retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet as East Side Story, a rivalry between Lower East Side Jewish and Catholic teens set during the convergence of Passover and Easter. The creative team, all Jews, reworked their project for Sharks and Jets—transferring their Jewish “otherness” onto Puerto Rican Sharks seeking recognition as full Americans by the Jets.

Perhaps picking up on Bernstein’s efforts to confront the racial violence of his day, theater critic Brooks Atkinson wrote: “The subject is not beautiful. But what ‘West Side Story’ draws out of it is beautiful. For it has a searching point of view.”

Vietnam Era

The Vietnam War, the draft, shootings at Kent State, the May Lai Massacre, and the imprisonment of outspoken antiwar activists led a generation of Americans into a deep reckoning with faith in humanity and in our nation’s leaders.

Witnessing these events, Bernstein confronted his own faith in God and government, turning to the power of prayer and music to bring peace to turbulent times. He pulled no punches in wrestling with faith in his tour de force, MASS.

America’s ongoing struggle for civil rights and civil liberties and the complexities of American military intervention abroad inspired Bernstein’s work during the 1960s and ‘70s and remains relevant for 21st-century listeners.

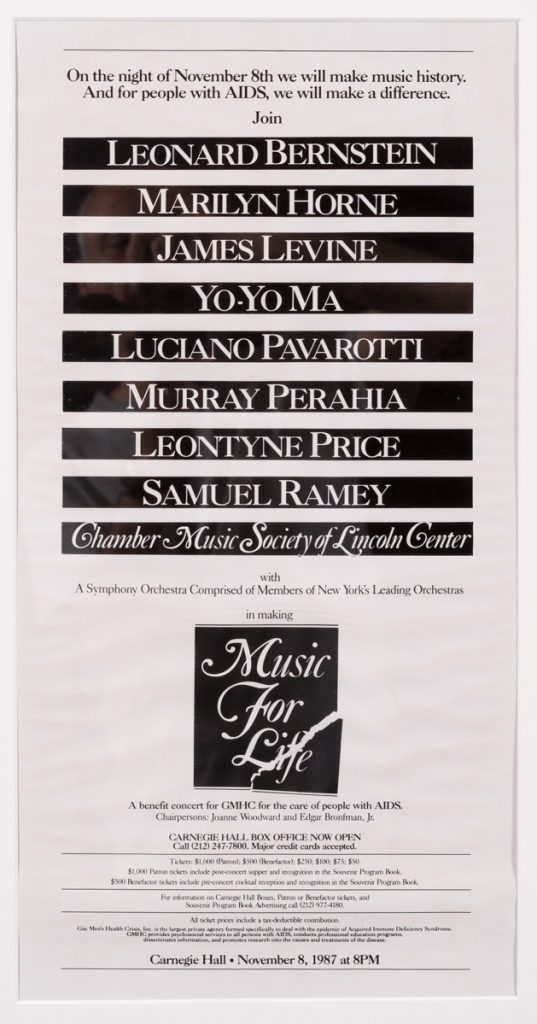

Lenny’s Legacy

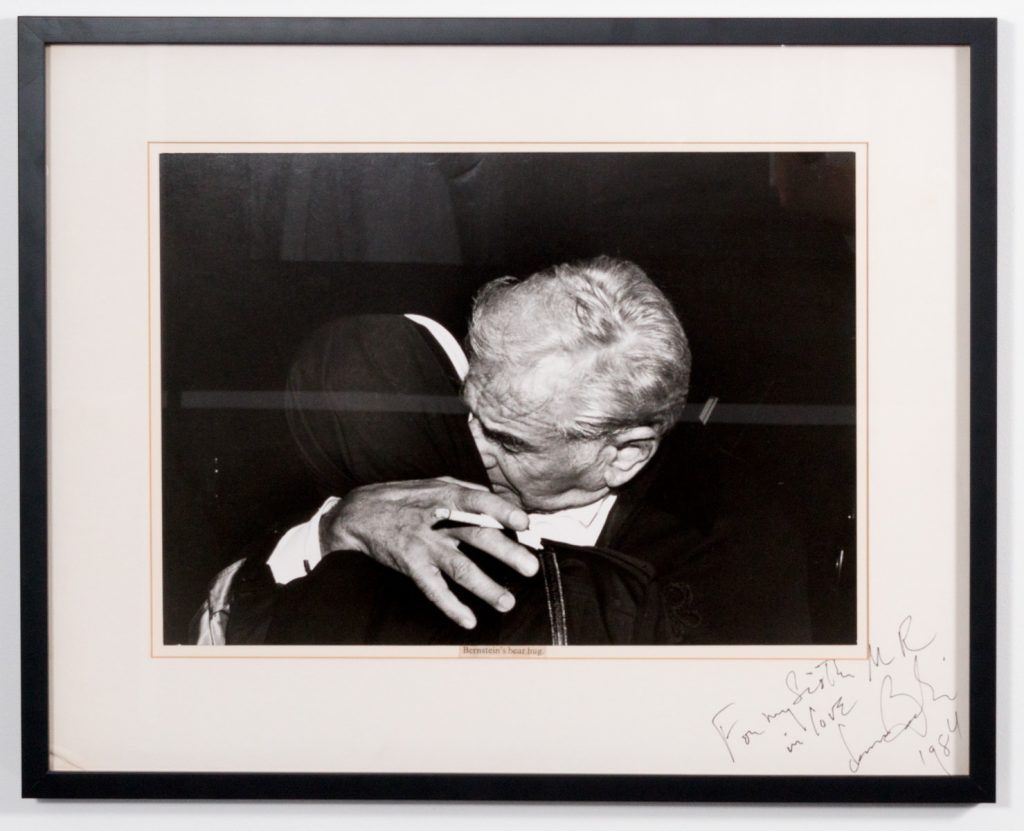

His hair.

His humor.

His humanity.

Leonard Bernstein’s colleagues, protégés, and friends remember him beyond his brilliance as a composer or conductor, tireless educator, or consummate humanitarian. Bernstein’s music held the solution to the 20th-century crisis of faith. He just had to find the right tune.

For his fans in the seats—at Carnegie Hall, Tanglewood, and concert halls around the world—Bernstein’s presence on the podium was just as memorable as the notes he summoned from the keyboard or the baton. Just listen to the stories they tell.

Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music was orchestrated by the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia and made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor. Key support provided by The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation. Major support provided by The Asper Foundation; CHG Charitable Trust as recommended by Carole Haas Gravagno; The Harvey Goodstein Charitable Foundation; Lindy Communities; The Leslie Miller and Richard Worley Family Foundation; and Cheryl and Philip Milstein. Additional support provided by Judith Creed and Robert Schwartz; Jill and Mark Fishman; Robert and Marjie Kargman; David G. and Sandra G. Marshall; Robin and Mark Rubenstein; and The Savitz Family Foundation. Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein Office; the Bernstein Family; Jacobs Music; and the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, and USC Shoah Foundation.

The virtual tour of Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music was made possible through the generous support of

George S. Blumenthal.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.